Stocks get all the attention. They have the big, flashy returns, there’s always something happening, and you can use them to tell pretty much any story you want about the markets.

Bonds may not be as flashy, but they form the bedrock of your portfolio. They are the anchor that keeps your investments grounded while your stocks are blown about by the daily whims of the markets.

The most interesting thing about bonds is how incredibly boring they are. A stock is a tiny sliver of ownership in a particular company. The returns may come at some point, but there’s no way to know when or how much you’ll get. But a bond is a contract that says you will be paid a specific amount of money at a specific time.

That means that, to a large extent, if you hold a bond to maturity, you know exactly what you are getting when you buy a bond (assuming the issuer doesn’t default). This says a lot about what bond returns look like and – as a result – how they should be incorporated into your investment portfolio.

This quarter, we want to do a deep dive on how to think about bonds, and the role they play in your portfolio.

The Sources of Bond Risks and Returns

The Sources of Bond Risks and Returns

As I said, if you hold a bond to maturity, its returns are largely predetermined. As long as the issuer doesn’t stop paying off the bond, then you know exactly what your returns will be.

The returns don’t require much in the way of explanation – they were determined by the price you paid when you bought the bond, so you don’t need to worry about what the markets are doing. Holding bonds to maturity – especially in the context of a bond ladder designed to meet future expenses – can often make a lot of sense.

If we don’t hold a bond until maturity, we introduce uncertainty into the system. Not holding bonds until maturity means we’ll eventually sell it into the market, and we need to worry about what another investor will be willing to pay for it.

But even then, we still know a lot about the returns we’ll see – no matter what happens (again assuming the issuer doesn’t default on the bond), we still know what the cash flows coming off of the bond will be. The question is how much another investor will pay for the remaining cash flows from the bond when we sell it.

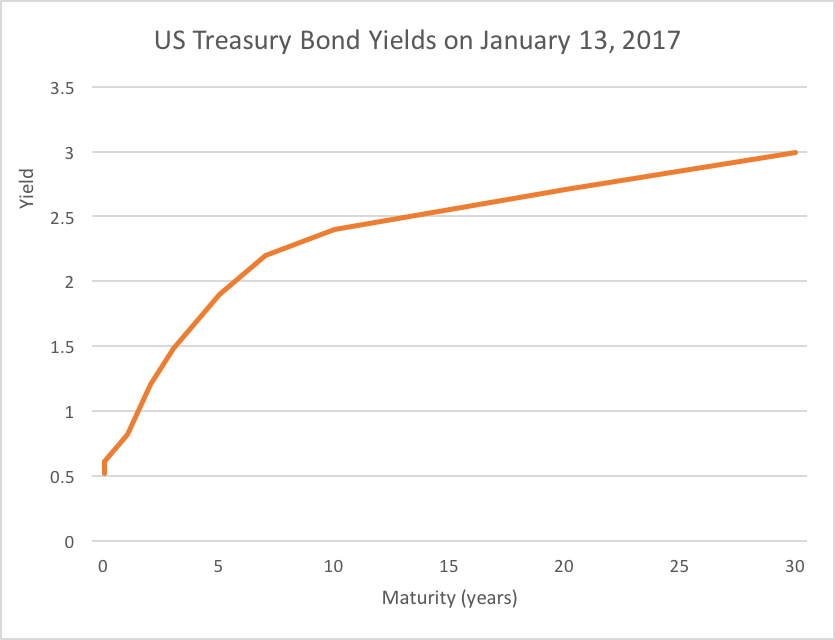

Before we go any further, I want to stop and talk a little about how you look at the bond market. You’ve probably heard the term “Yield Curve” before. It’s usually talked about as this mythical thing that the Fed wields like a bull whip.

Like a lot of finance stuff, the reality is a lot more prosaic. The yield curve is just what the return of similar bonds (held to maturity) from the same issuer cost at different maturities.

Let’s think about the yield curve of the US Treasury – there aren’t many large maturity gaps there since they are pretty much continually issuing bonds. This means that its yield curve will be pretty continuous, though not necessarily smooth. Let’s look at an example:

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

Data provided by US Department of the Treasury

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

This is what the yield curve for US Treasury bonds looked like on Friday, January 13, 2017. There’s nothing magical about it – it’s just a description of what these bonds were trading at the different maturities in the market. That being said, it’s an incredibly useful tool. This chart gives us all sorts of information about what bond returns look like.

However, you’ll probably notice that we’re not looking at a particularly recent yield curve. That’s because since late 2022 we have been seeing something that is called an inverted yield curve. This is where the yield on shorter bonds is actually higher than the yield on longer term bonds. While this is unusual (and goes against most people’s intuition of how the bond market is supposed to work), it’s not unprecedented.

So let’s start breaking them down.

Breaking Down Bond Returns

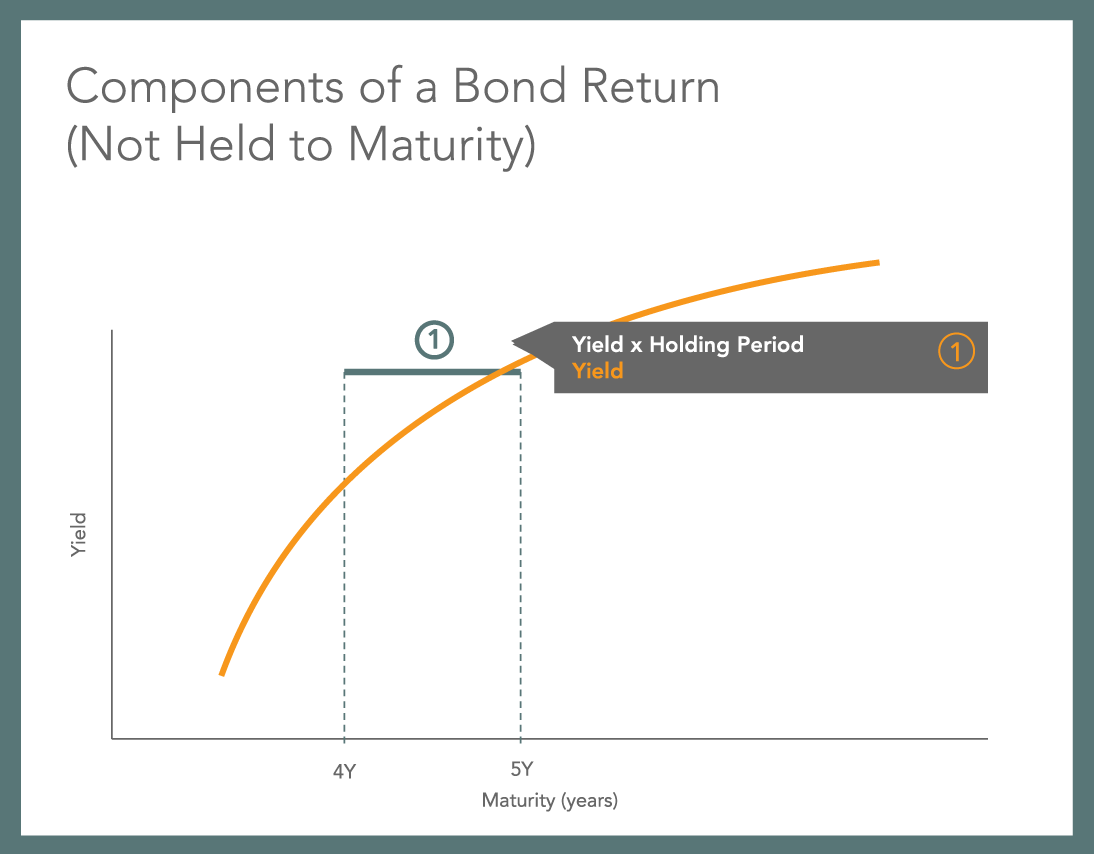

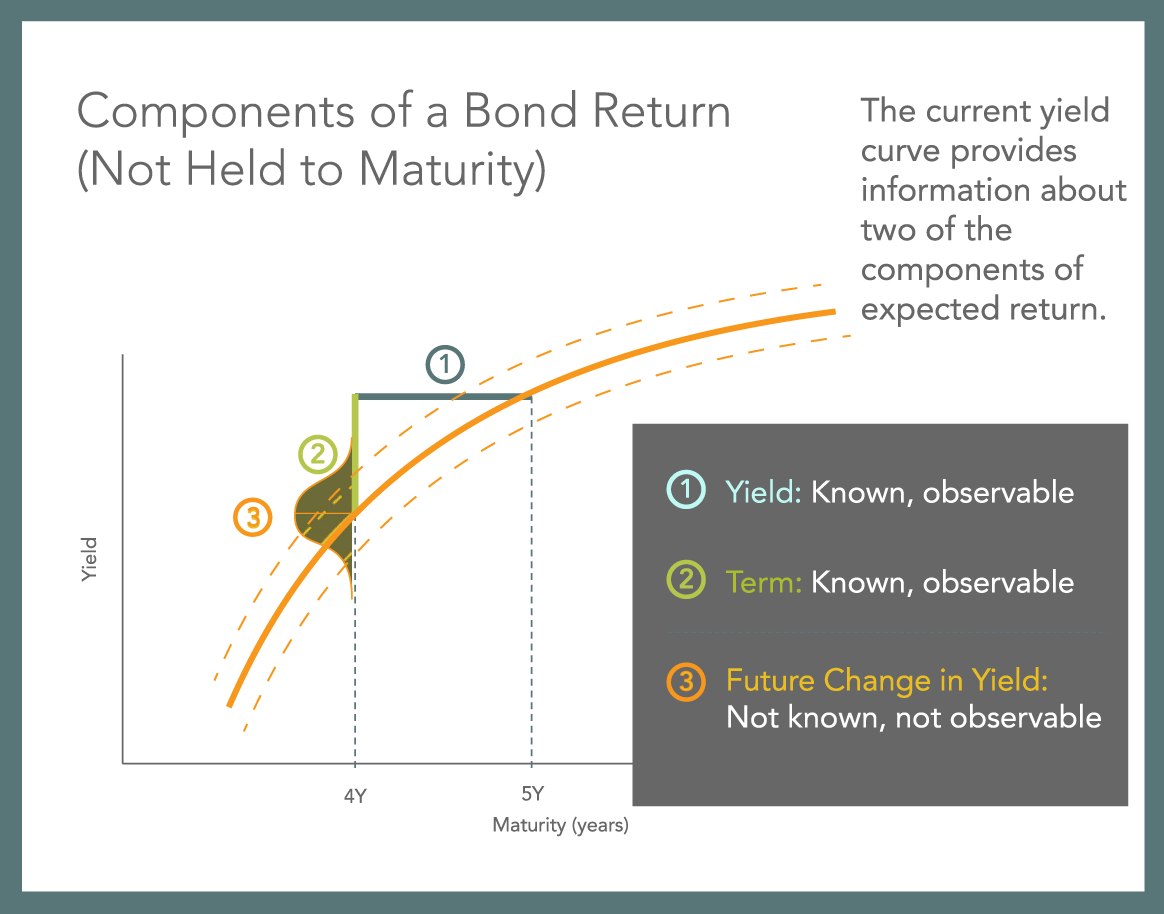

If we aren’t holding a bond to maturity, there are three components to a bond’s returns:

- Cash Flow Return

- Change in Term

- Changes in the Yield Curve

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

Cash Flow Return

Your cash flow return is what you get from the cash flows that the bond is putting out. Since you know what the cash flows will be (with some notable exceptions like TIPS), and you know what you paid, you know what this piece of the return will be.

Using the yield curve as our guide, if we hold a five-year bond for one year, the return we get from the bond’s yield is equal to the five-year yield listed on the curve times the holding period of one year.

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

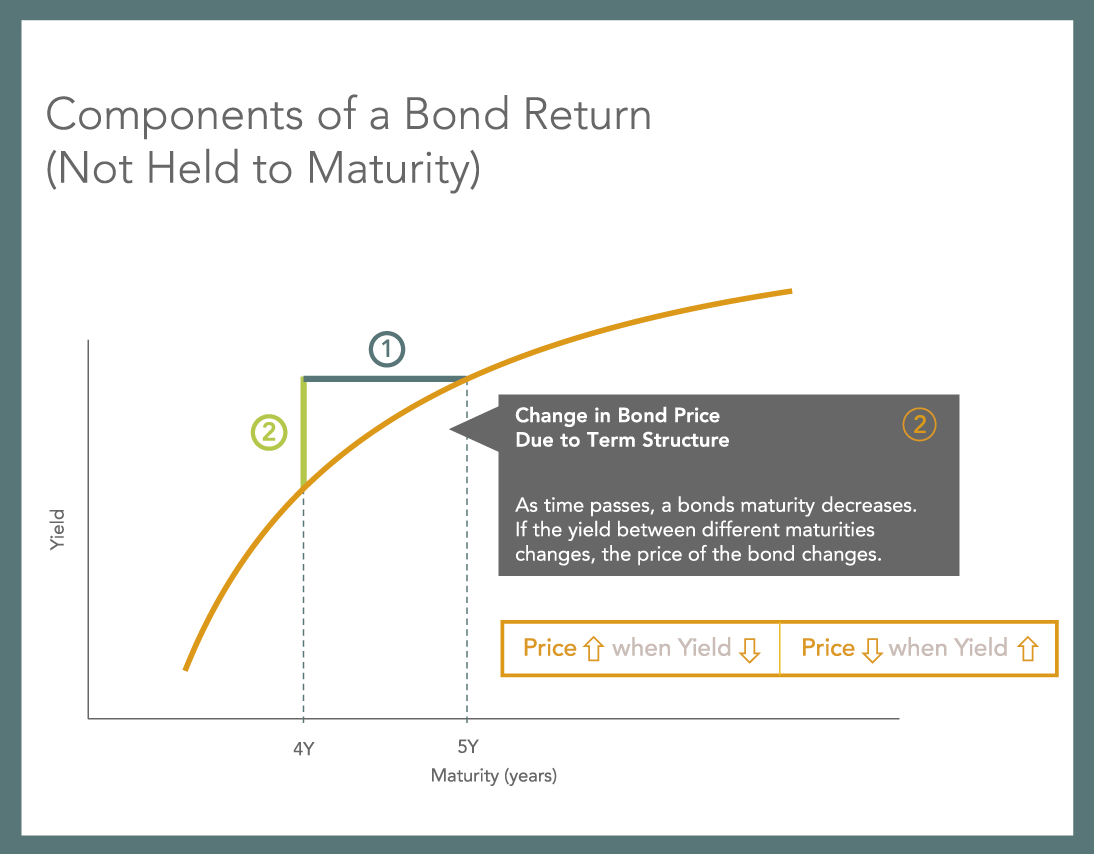

Change in Term

The term component is the change in the price of the bond based on how it will move through the current yield curve. This is ( big part of) the capital gains piece of a bond’s return. For most bonds, the repayment of principle at maturity is the biggest part of the bond’s cash flows.

People are willing to pay more for a bond as it gets closer to the big principle payment at maturity. They don’t have to wait as long. Since this part is based on today’s yield curve, we know what this piece of the return is going to be. We need to use an equation to describe the expected capital gain or loss, but it’s not too complicated:

We haven’t discussed duration yet, but you can think of it as how sensitive a bond is to interest rate moves.

The important thing to take away from this is that, just like a bond’s yield, we have a really good idea of what the expected return from this piece is going to be even before we buy a bond. This piece of the return is both known and observable.

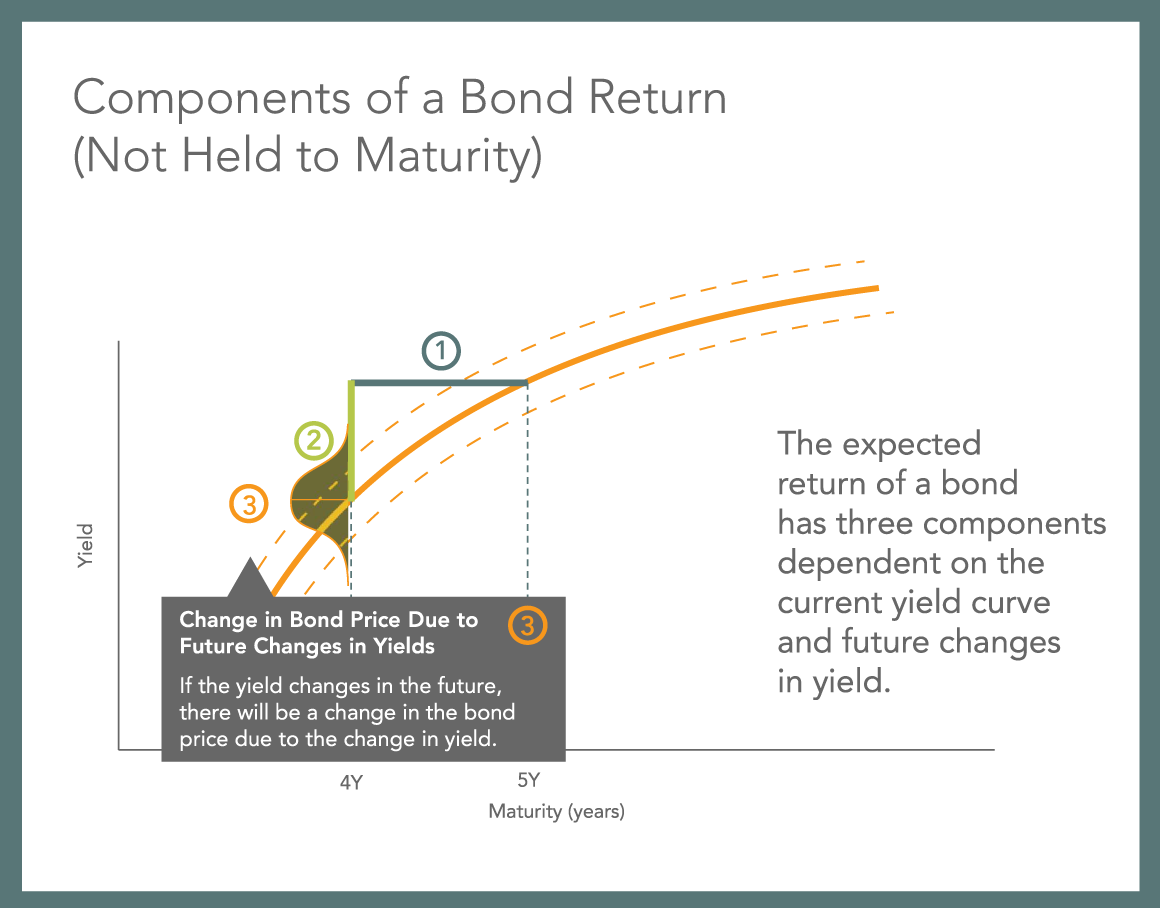

Changes in the Yield Curve

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

This is where we bring in the uncertainty. When we looked at the term piece of the return, we were assuming that the yield curve was static. That’s obviously not the case. Since the yield curve is just a description of what the market looks like, it’s constantly changing.

The yield curve looks different now than it did when you started reading this article. But just like with stocks, we don’t know where the yield curve is heading next. The best predictor of future interest rates is today’s interest rates (although this doesn’t mean they’re particularly good predictions, they’re just the best we have).

So the expected return from the future changes in the yield curve is assumed to be essentially zero. When we’re buying a bond, the future moves are noise – future pprices are equally likely to go up or down.

That being said, the yield curve will end up moving one way or the other, and that will have an effect on the price the next investor will be willing to pay for the bond.

Putting it all together, we end up with a picture that looks like this:⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

We have a pretty good idea of what the yield and term returns will be, but we don’t know what the third piece will look like. This uncertainty is some of the risk you face when you invest in bonds, but not all of it. So let’s take a look at the risks to bond investing.

Bond Risk Factors

Almost everything we’ve discussed up until now has left out a massively important part of the story – risk. You can’t have returns without taking on more risk (at least not any greater than the risk-free rate). And, unfortunately, ignoring it does not make the risk go away.

But understanding the risks that you face with bonds is actually pretty straightforward. There are only two risk factors you need to pay attention to:

- Interest Rate Risk (sometimes called “term” or “maturity” risk)

- Default Risk

Interest Rate Risk

This is essentially the chance that interest rates will rise, and the bonds you own will be worth less in the future. As a bond’s time until maturity lengthens, the effects of interest rate movements on them increases.

A half-percent increase in rates will hurt a twenty-year bond a lot more than a three-month bond, and investors need to be compensated for taking on this risk. Otherwise you would just keep rolling over one-month treasury bills.

What’s really interesting about interest rate risk is that you can see exactly how much you are being compensated for it. The compensation is the yield curve. We can plot out what the difference in expected return is between any combination of bonds you want, and then decide if the additional return is worth it to take on the additional risk.

Normally – though not always – we have an upward-sloping yield curve (like the one we looked at earlier). This means you have a higher expected annual return on a twenty-year bond than you do on a one-year bond. If there was no interest rate risk, then – at least to a first approximation – you would have roughly the same expected annual return on a one-year bond and a twenty-year bond.

Default Risk

If interest rate risk is pretty easy to understand, default risk is even easier. It’s the risk that the bond issuer won’t pay you back. When you hear people talk about credit ratings of companies or governments, this is what those ratings are measuring – how likely they are to pay bond holders back. Measuring this is not quite as clean or straightforward as interest rate risk, but we can tease it out pretty well.

If we’re worried that someone isn’t likely to pay us back, we demand a higher interest rate when we loan them money. It’s exactly the same for bonds (essentially, a bond is just a loan – it’s just for more money and there are more contracts involved).

Let’s say the US government and K-Mart both issue ten-year bonds today. The government’s interest rate would likely be a lot lower than K-Mart would have to offer to raise the same amount of money. I feel very comfortable saying the US government will be around in ten years to pay me back, but I feel a lot less sure about K-Mart.

The debts of the US government are backed by the full faith and credit of the entire US government (and, more importantly, its taxing power). K-Mart’s debts are backed by blue light specials.

But let’s take this one step further. Let’s say we have a situation where, because the bonds were issued at different times, we have two bonds with the same maturity and coupon from the US government and K-Mart. In this situation you would still not be as comfortable holding the K-Mart bond.

There’s always the chance that K-Mart will default on its obligations (there’s a chance the US Treasury could default, but it’s pretty remote), and you need to be compensated for that as an investor. The K-Mart bond has to promise a higher expected return to get you to prefer it over the US government bond. That additional return is achieved by not paying as much for the K-Mart bond.

Since the market isn’t willing to pay as much for the cash flows coming from K-Mart, that makes the return on its bond higher. This difference in return between K-Mart and US government bonds is called the “credit spread,” and it’s the best measure of default risk. Traditionally, corporate bonds are measured against their home country’s government, or a US Treasury bond of the same maturity, but you can compare any two securities you like.

So now that we have the three sources of bond returns and two bond risk factors, what do we do with this? It’s great to be able to model out bond returns and draw pretty diagrams, but how does that impact you? What does it mean for your financial plan? What does it mean for how you should use bonds in your portfolio?

The Role of Bonds in Your Investment Portfolio

Bonds are the ballast of your portfolio. They help keep your portfolio on an even keel by allowing you to (reasonably) easily and (reasonably) precisely target the level of risk you want in your portfolio. Getting the level of risk in your portfolio right is the most important thing you can do when investing.

Building your portfolio around risk tolerance is a big help when it comes to staying disciplined and focused on your larger goals. If you’re worried about the day to day, month to month, or quarter to quarter market oscillations, you’re going to be pulled off track. You’re going to fall into the fear and greed cycle, and nothing good ever comes from there.

When you direct your portfolio according to your emotions or what you think will happen next in the markets, you’re setting yourself up for some rather painful losses. Building a portfolio that will help you stay disciplined during good and bad markets is what separates investors who will likely have a good investment experience from those who won’t.

And your stock to bond ratio is the main risk lever in your portfolio.

Bonds are there to balance out your stocks. Stocks are better at delivering the returns you want out of your portfolio, but they’re also a lot riskier. Your bonds help you rein in that risk so you end up with a portfolio that will help you stay disciplined over the long term.

Like this article? Download our free eBook!

Our eBook The 9 Secrets of Intelligent Investors breaks down the guiding principles to help you make informed investment decisions.